Latest on MJJC

- Latest Michael Jackson News

- Click Here to Join Our Community

- Follow us on Twitter

- Wanna talk Michael? Come join the chat rooms

- The Michael Jackson Chart Watch

- Become an MJJC Patron

- Join the Premium Member Group and Get Lot's of Extra's

- Major Love Prayer - Worldwide Monthly Prayer Every 25th

- MJJC Exclusive Q&A - We talk to the family and those in and around Michael

- Join us in the Chat Rooms

- Find us on Facebook

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

My Next Book: Michael Jackson, Inc. Zack O'Malley Greenburg, Forbes Staff

- Thread starter Bubs

- Start date

‘Michael Jackson, Inc’ Celebrates The King Of Pop’s Business Savvy

Source: The Grio – By Andrea J. Castillo

Michael Jackson is by far one of the most iconic entertainers of our time, an icon who created a signature sound that we will never be duplicated.

After his death in 2009 at the age of 50, his musical legacy and business savvy were often overshadowed by his personal problems.

Author Zach O’Malley Greenburg looks to right that wrong in his forthcoming biography, Michael Jackson, Inc., which gives MJ fans some insight into why “The King Of Pop” was more than just a trailblazer in music, but in business as well.

Born and raised in New York City and a proud product of the hip-hop generation (he recounts one of his first musical purchases being Puff Daddy & The Family’s No Way Out), Greenburg has reported on how some the genre’s biggest stars make their money. As a senior editor for Forbes, Greenburg has been quite influential in letting us know the scoop behind top earners in hip-hop via the extremely popular annual Cash Kings list; a list that has been offering bragging rights to emcees since 2007.

“My career really started with hip-hop, and it’s fun to see as I’ve been covering it, it’s grown more and more into the mainstream,” said Greenburg.

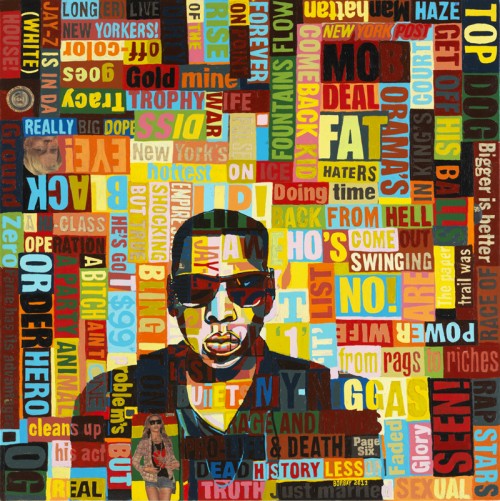

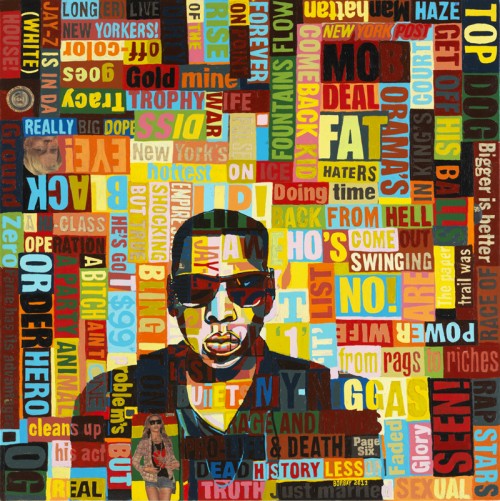

In 2012, Greenburg released his first book entitled Empire State of Mind: How Jay-Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office, an in-depth exploration of how Jay Z became the mogul he is today. While writing this book, Greenburg became acquainted with Borbay, a New York based pop artist whom shared his love of hip-hop.

Says Greenburg: “I met Borbay a couple of years ago and he had seen the hip-hop ‘Cash Kings’ package. He kinda came across it because he had just done an exhibition called the ‘Kings of Hip-Hop’, which were his renditions of the most important figures in the genre. As a coincidence, they happened to be almost completely overlapping with the top seven earners in hip-hop on my Cash Kings list.”

This chance meeting evolved into a friendship that would lead the two to work together in the not too distant future.

Fast forward a year and Greenburg is working on a second book, Michael Jackson Inc., a retrospective of the Michael Jackson empire, aided by 100 never-before-told interviews of some of the industry’s biggest names, including the likes of Berry Gordy, 50 Cent, Sheryl Crow, and many more. He developed the angle for his book in the wake of Jackson’s death while covering the value of the Sony ATV catalogue Jackson had acquired in the mid-1980s.

“As I went on with that story, and the business of MJ and his financial life after death, the astounding amount of money he’s made since he died, over $700 million. That is more than any single living act has made over that period of time,” said Greenburg.

Greenburg believes that Jackson “was a trailblazer in the monetization of fame,” having been one of the first artists to have their own shoe line, a clothing line, and have a label simultaneously.

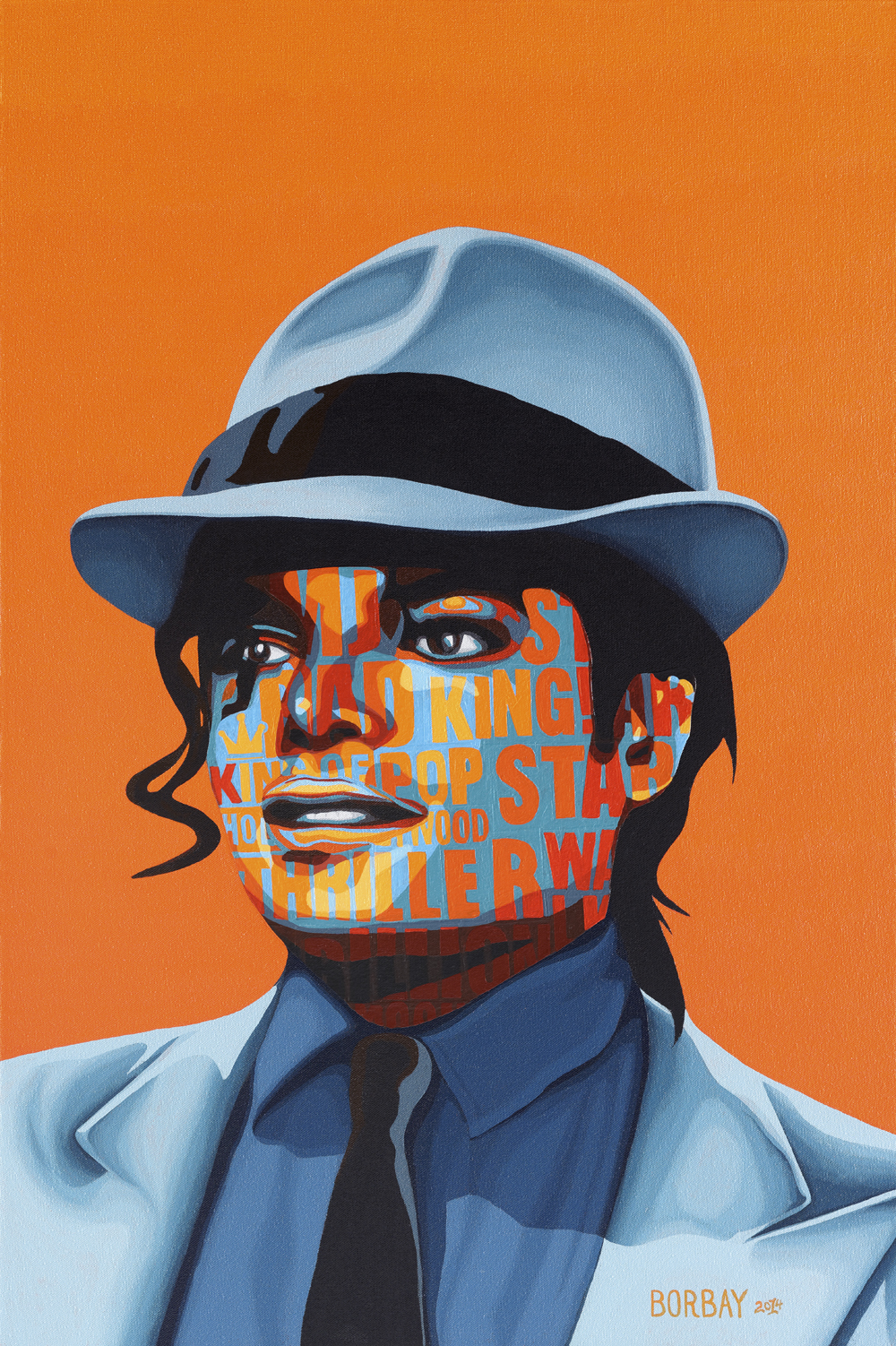

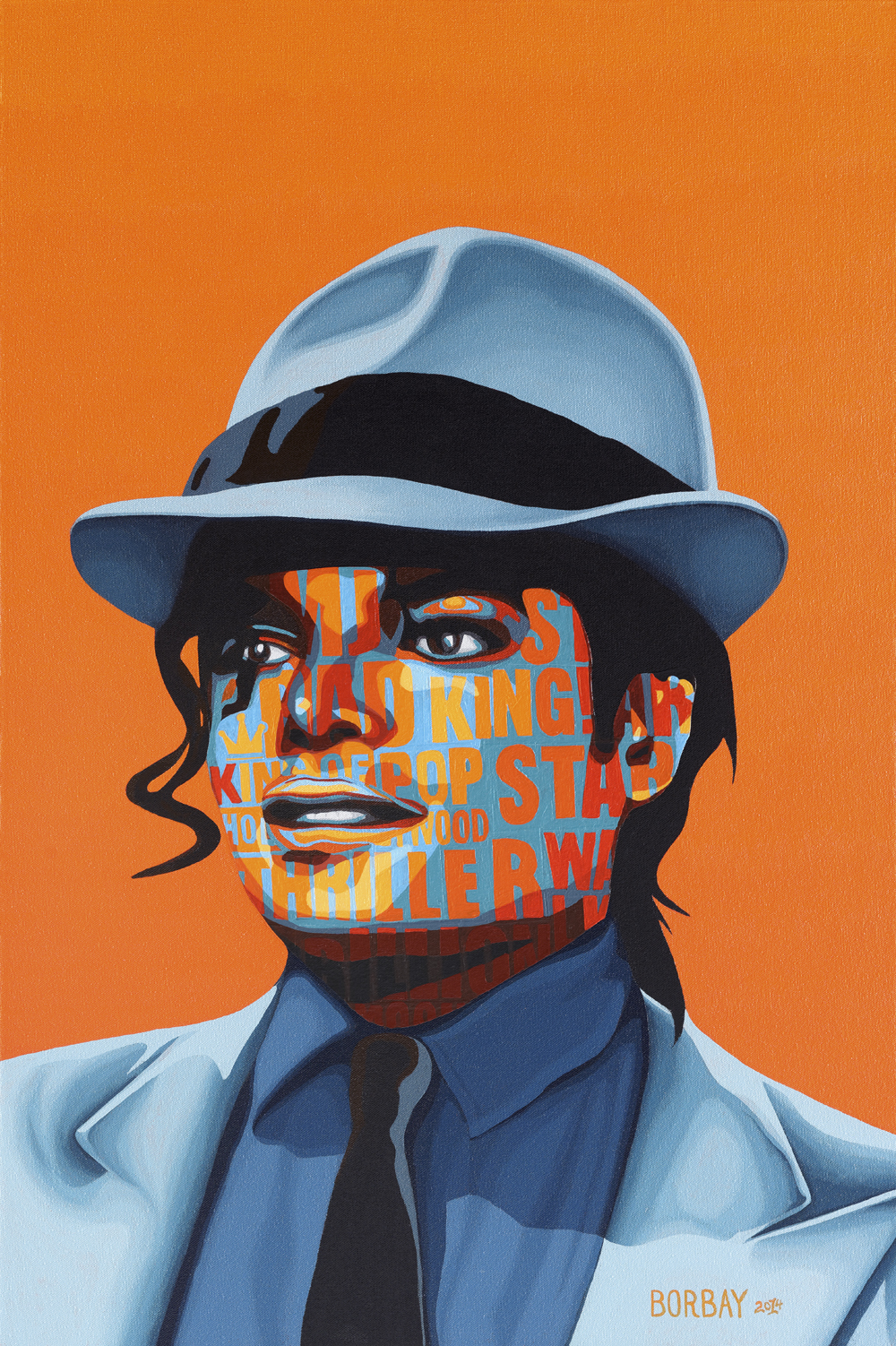

He tapped Borbay to collaborate on a cover image for the book. The end result was a bold painted portrait of the King of Pop at the height of his fame during the Bad era, layered with New York Post headlines on the face, projecting popular opinion on the iconic singer.

Greenburg hopes his book will open the eyes of Jackson fans of all walks of life to his business acumen.

“He laid the groundwork for this, and I think a lot of people forget or never even knew what a good businessman he was because of the late life struggles.”

Michael Jackson, Inc.: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of a Billion-Dollar Empire will be released on June 3, 2014. It is now available for pre-order at mjinc.co.

Source: The Grio – By Andrea J. Castillo

Michael Jackson is by far one of the most iconic entertainers of our time, an icon who created a signature sound that we will never be duplicated.

After his death in 2009 at the age of 50, his musical legacy and business savvy were often overshadowed by his personal problems.

Author Zach O’Malley Greenburg looks to right that wrong in his forthcoming biography, Michael Jackson, Inc., which gives MJ fans some insight into why “The King Of Pop” was more than just a trailblazer in music, but in business as well.

Born and raised in New York City and a proud product of the hip-hop generation (he recounts one of his first musical purchases being Puff Daddy & The Family’s No Way Out), Greenburg has reported on how some the genre’s biggest stars make their money. As a senior editor for Forbes, Greenburg has been quite influential in letting us know the scoop behind top earners in hip-hop via the extremely popular annual Cash Kings list; a list that has been offering bragging rights to emcees since 2007.

“My career really started with hip-hop, and it’s fun to see as I’ve been covering it, it’s grown more and more into the mainstream,” said Greenburg.

In 2012, Greenburg released his first book entitled Empire State of Mind: How Jay-Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office, an in-depth exploration of how Jay Z became the mogul he is today. While writing this book, Greenburg became acquainted with Borbay, a New York based pop artist whom shared his love of hip-hop.

Says Greenburg: “I met Borbay a couple of years ago and he had seen the hip-hop ‘Cash Kings’ package. He kinda came across it because he had just done an exhibition called the ‘Kings of Hip-Hop’, which were his renditions of the most important figures in the genre. As a coincidence, they happened to be almost completely overlapping with the top seven earners in hip-hop on my Cash Kings list.”

This chance meeting evolved into a friendship that would lead the two to work together in the not too distant future.

Fast forward a year and Greenburg is working on a second book, Michael Jackson Inc., a retrospective of the Michael Jackson empire, aided by 100 never-before-told interviews of some of the industry’s biggest names, including the likes of Berry Gordy, 50 Cent, Sheryl Crow, and many more. He developed the angle for his book in the wake of Jackson’s death while covering the value of the Sony ATV catalogue Jackson had acquired in the mid-1980s.

“As I went on with that story, and the business of MJ and his financial life after death, the astounding amount of money he’s made since he died, over $700 million. That is more than any single living act has made over that period of time,” said Greenburg.

Greenburg believes that Jackson “was a trailblazer in the monetization of fame,” having been one of the first artists to have their own shoe line, a clothing line, and have a label simultaneously.

He tapped Borbay to collaborate on a cover image for the book. The end result was a bold painted portrait of the King of Pop at the height of his fame during the Bad era, layered with New York Post headlines on the face, projecting popular opinion on the iconic singer.

Greenburg hopes his book will open the eyes of Jackson fans of all walks of life to his business acumen.

“He laid the groundwork for this, and I think a lot of people forget or never even knew what a good businessman he was because of the late life struggles.”

Michael Jackson, Inc.: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of a Billion-Dollar Empire will be released on June 3, 2014. It is now available for pre-order at mjinc.co.

Annita

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2011

- Messages

- 3,177

- Points

- 113

Zack O. Greenburg ‏@zogblog 14. Apr.

“He had a kid’s heart, but a mind of a genius.” -Berry Gordy on @MichaelJackson, from my MJ bio. Preorder: http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

Zack O. Greenburg ‏@zogblog 14. Apr.

Starting today, I'll tweet a quote once a week from my King of Pop business bio "Michael Jackson, Inc," due out 6/3. Stay tuned! #MJMondays

____

Michael Jackson, Inc.

21. April

MJ Mondays returns! Here’s the latest snippet from Michael Jackson, Inc. It’s a quote from Swizz Beatz, who was working with MJ toward the end of his life. “I was going to bring my wife [Alicia Keys] in to write, and we were going to do one big collaboration,” the producer recalls. “He was a big fan of hers. I heard he had a crush on her, so I was like, ‘Wow, MJ got a crush on my wife!’ . . . It was getting ready to become a great recipe.” Pre-order the book: http://mjinc.co/

“He had a kid’s heart, but a mind of a genius.” -Berry Gordy on @MichaelJackson, from my MJ bio. Preorder: http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

Zack O. Greenburg ‏@zogblog 14. Apr.

Starting today, I'll tweet a quote once a week from my King of Pop business bio "Michael Jackson, Inc," due out 6/3. Stay tuned! #MJMondays

____

Michael Jackson, Inc.

21. April

MJ Mondays returns! Here’s the latest snippet from Michael Jackson, Inc. It’s a quote from Swizz Beatz, who was working with MJ toward the end of his life. “I was going to bring my wife [Alicia Keys] in to write, and we were going to do one big collaboration,” the producer recalls. “He was a big fan of hers. I heard he had a crush on her, so I was like, ‘Wow, MJ got a crush on my wife!’ . . . It was getting ready to become a great recipe.” Pre-order the book: http://mjinc.co/

Annita

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2011

- Messages

- 3,177

- Points

- 113

https://twitter.com/zogblog

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 36 Min.

“He was so far advanced in the way he thought about things.” @Pharrell on @MichaelJackson for my MJ bio http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 20 Std.

"It’s a modern, pop version of Citizen Kane.” - @SteveForbesCEO on my new book, @MichaelJackson Inc. Pre-order here: http://mjinc.co

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 28. Apr.

“I don’t want to lose the deal…IT’S MY CATALOGUE.” -@MichaelJackson on buying Beatles/ATV, from my MJ bio http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 36 Min.

“He was so far advanced in the way he thought about things.” @Pharrell on @MichaelJackson for my MJ bio http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 20 Std.

"It’s a modern, pop version of Citizen Kane.” - @SteveForbesCEO on my new book, @MichaelJackson Inc. Pre-order here: http://mjinc.co

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 28. Apr.

“I don’t want to lose the deal…IT’S MY CATALOGUE.” -@MichaelJackson on buying Beatles/ATV, from my MJ bio http://mjinc.co #MJMondays

http://www.forbes.com/sites/zackoma...n-dollar-career-earnings-listed-year-by-year/

Michael Jackson’s Multibillion Dollar Career Earnings, Listed Year By Year

Michael Jackson’s latest posthumous album, Xscape, debuted earlier this month with opening week sales of 157,000, landing at No. 2 on the Billboard albums chart. That will undoubtedly fatten the total amount the King of Pop has raked in since his death—well over $700 million in the past five years.

But Jackson earned far more than that during his life, thanks both to his musical prowess and his far less celebrated business savvy. In addition to releasing the best-selling album of all time and grossing hundreds of millions of the road, Jackson paved the way for modern musician-moguls by launching his own sneakers, clothes, video games and other ventures.

His lifetime total: $1.1 billion, or just shy of $2 billion when accounting for inflation. Add adjusted posthumous figures, and the number soars to nearly $3 billion.

“He was extremely smart,” says rapper-actor-entrepreneur Christopher “Ludacris” Bridges. “From my perspective, because I’m business-oriented and savvy, I noticed and even read up on everything he did.”

Jackson helped create a fundamental shift in the monetization of fame, and that’s the notion at the core of my book, Michael Jackson, Inc, the first business-focused biography of the King of Pop, which will be published on June 3rd by Simon & Schuster’s Atria imprint.

At the end of the book is a table of annual earnings estimates for Jackson’s entire adult solo career, formulated by talking to over 100 entertainment industry insiders over the course of two years. But today, FORBES readers get a sneak peek at that research.

Highlights include the $134 million he made in the two years after the release of Thriller (an inflation-adjusted $306 million), the $125 million he banked in 1988 at the height of the Bad Tour (an inflation-adjusted $247 million), and the $118 million he earned in 1995 after scoring a nine-figure payout for merging his ATV publishing catalogue with Sony ’s own (an inflation-adjusted $181 million).

“He had good instincts . . . more, more, more; better, better, better,” says manager Sandy Gallin, who managed Jackson for much of the 1990s. “He would, in his mind, negotiate the same way. No matter what anybody would offer, he wanted more.”

Jackson’s earnings prowess was so great that, even after child molestation allegations rocked his career in 1993, he recovered and had one of his best years ever in 1995. But after a second round of accusations turned into a lengthy trial in 2005, the King of Pop was unable to regain his peak financial form—in his lifetime, that is.

Only after his sudden death in 2009 did Jackson once again start earning nine-figure sums annually. The executors of his estate scored a whopping $250 million new record deal from Sony, released concert film This Is It (which grossed over $260 million), and launched two Cirque du Soleil shows.

Jackson’s postmortem totals were also boosted significantly by earnings from the assets he accumulated in life—namely, the Sony/ATV publishing catalogue that contains the copyrights to most of the Beatles’ biggest hits, as well as other songs by the likes of Lady Gaga, Eminem and Taylor Swift.

Today, Jackson’s heirs still own half of that company, worth about $2 billion, through his estate. The King of Pop purchased the catalogue’s core in 1985 for $47.5 million, and it adds tens of millions to his bottom line every year.

“He had a kid’s heart, but a mind of a genius,” Berry Gordy told me in an interview for Michael Jackson, Inc. “He was so loving and soft-spoken, and a thinker. . . . He wanted to do everything, and he was capable. You can only do so much in a lifetime.”

Michael Jackson’s Multibillion Dollar Career Earnings, Listed Year By Year

Michael Jackson’s latest posthumous album, Xscape, debuted earlier this month with opening week sales of 157,000, landing at No. 2 on the Billboard albums chart. That will undoubtedly fatten the total amount the King of Pop has raked in since his death—well over $700 million in the past five years.

But Jackson earned far more than that during his life, thanks both to his musical prowess and his far less celebrated business savvy. In addition to releasing the best-selling album of all time and grossing hundreds of millions of the road, Jackson paved the way for modern musician-moguls by launching his own sneakers, clothes, video games and other ventures.

His lifetime total: $1.1 billion, or just shy of $2 billion when accounting for inflation. Add adjusted posthumous figures, and the number soars to nearly $3 billion.

“He was extremely smart,” says rapper-actor-entrepreneur Christopher “Ludacris” Bridges. “From my perspective, because I’m business-oriented and savvy, I noticed and even read up on everything he did.”

Jackson helped create a fundamental shift in the monetization of fame, and that’s the notion at the core of my book, Michael Jackson, Inc, the first business-focused biography of the King of Pop, which will be published on June 3rd by Simon & Schuster’s Atria imprint.

At the end of the book is a table of annual earnings estimates for Jackson’s entire adult solo career, formulated by talking to over 100 entertainment industry insiders over the course of two years. But today, FORBES readers get a sneak peek at that research.

Highlights include the $134 million he made in the two years after the release of Thriller (an inflation-adjusted $306 million), the $125 million he banked in 1988 at the height of the Bad Tour (an inflation-adjusted $247 million), and the $118 million he earned in 1995 after scoring a nine-figure payout for merging his ATV publishing catalogue with Sony ’s own (an inflation-adjusted $181 million).

“He had good instincts . . . more, more, more; better, better, better,” says manager Sandy Gallin, who managed Jackson for much of the 1990s. “He would, in his mind, negotiate the same way. No matter what anybody would offer, he wanted more.”

Jackson’s earnings prowess was so great that, even after child molestation allegations rocked his career in 1993, he recovered and had one of his best years ever in 1995. But after a second round of accusations turned into a lengthy trial in 2005, the King of Pop was unable to regain his peak financial form—in his lifetime, that is.

Only after his sudden death in 2009 did Jackson once again start earning nine-figure sums annually. The executors of his estate scored a whopping $250 million new record deal from Sony, released concert film This Is It (which grossed over $260 million), and launched two Cirque du Soleil shows.

Jackson’s postmortem totals were also boosted significantly by earnings from the assets he accumulated in life—namely, the Sony/ATV publishing catalogue that contains the copyrights to most of the Beatles’ biggest hits, as well as other songs by the likes of Lady Gaga, Eminem and Taylor Swift.

Today, Jackson’s heirs still own half of that company, worth about $2 billion, through his estate. The King of Pop purchased the catalogue’s core in 1985 for $47.5 million, and it adds tens of millions to his bottom line every year.

“He had a kid’s heart, but a mind of a genius,” Berry Gordy told me in an interview for Michael Jackson, Inc. “He was so loving and soft-spoken, and a thinker. . . . He wanted to do everything, and he was capable. You can only do so much in a lifetime.”

Zack O. Greenburg @zogblog · 14 h.

"@MichaelJackson Inc" named one of summer's hottest books (alongside titles by H Clinton, Stephen King) by @USAToday! http://www.usatoday.com/story/life/...king-george-rr-martin-liane-moriarty/9619055/ …

VIDEO - Michael Jackson: By The Millions: http://youtu.be/APi131y-AEs by @forbes

[video=youtube;APi131y-AEs]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APi131y-AEs[/video]

"@MichaelJackson Inc" named one of summer's hottest books (alongside titles by H Clinton, Stephen King) by @USAToday! http://www.usatoday.com/story/life/...king-george-rr-martin-liane-moriarty/9619055/ …

VIDEO - Michael Jackson: By The Millions: http://youtu.be/APi131y-AEs by @forbes

[video=youtube;APi131y-AEs]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APi131y-AEs[/video]

qbee

Proud Member

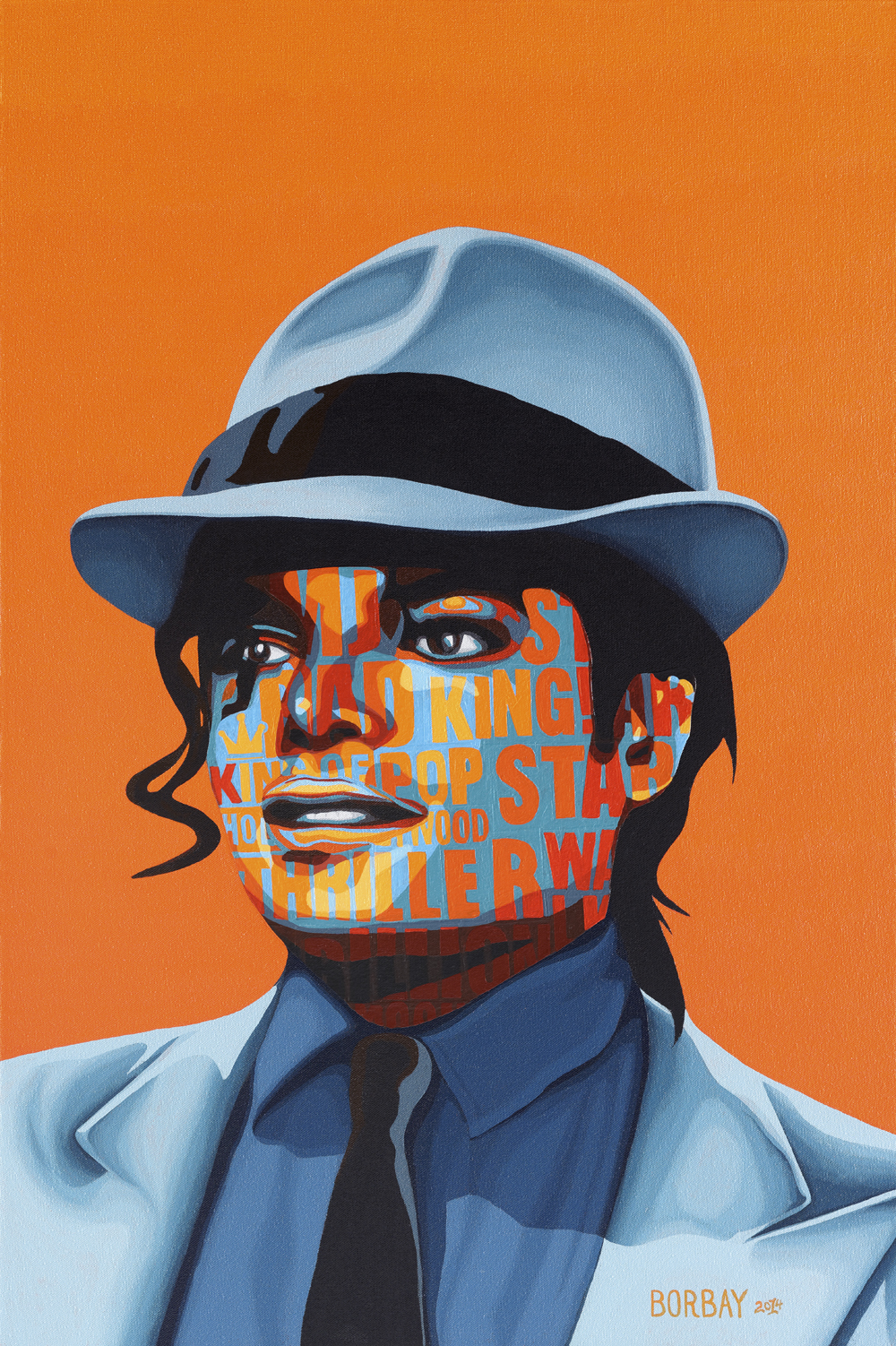

HQ painting .. of Michael Jackson Inc . Book Cover

Painting Details: Size: 24"X36" Media: Acrylic on Canvas

http://www.borbay.com/2014/02/24/borbay-paints-michael-jackson-inc-book-cover/

jason@borbay.com

Michael Jackson, Inc. Book Cover Painted by Borbay by Borbay

Painting Details: Size: 24"X36" Media: Acrylic on Canvas

http://www.borbay.com/2014/02/24/borbay-paints-michael-jackson-inc-book-cover/

jason@borbay.com

Michael Jackson, Inc. Book Cover Painted by Borbay by Borbay

Last edited:

qbee

Proud Member

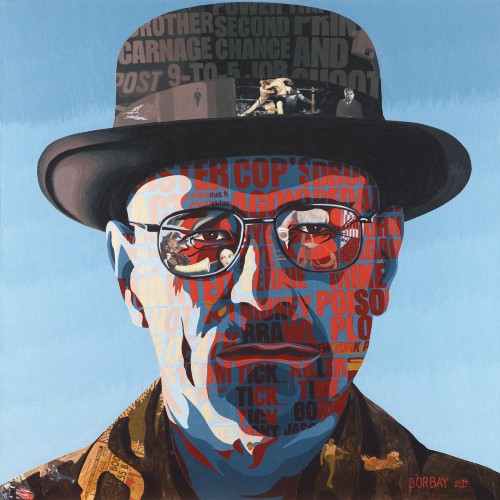

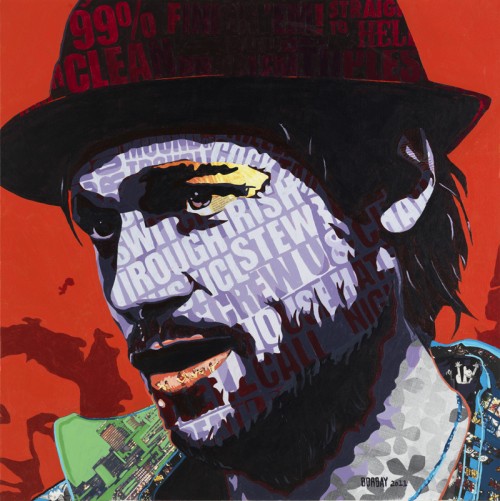

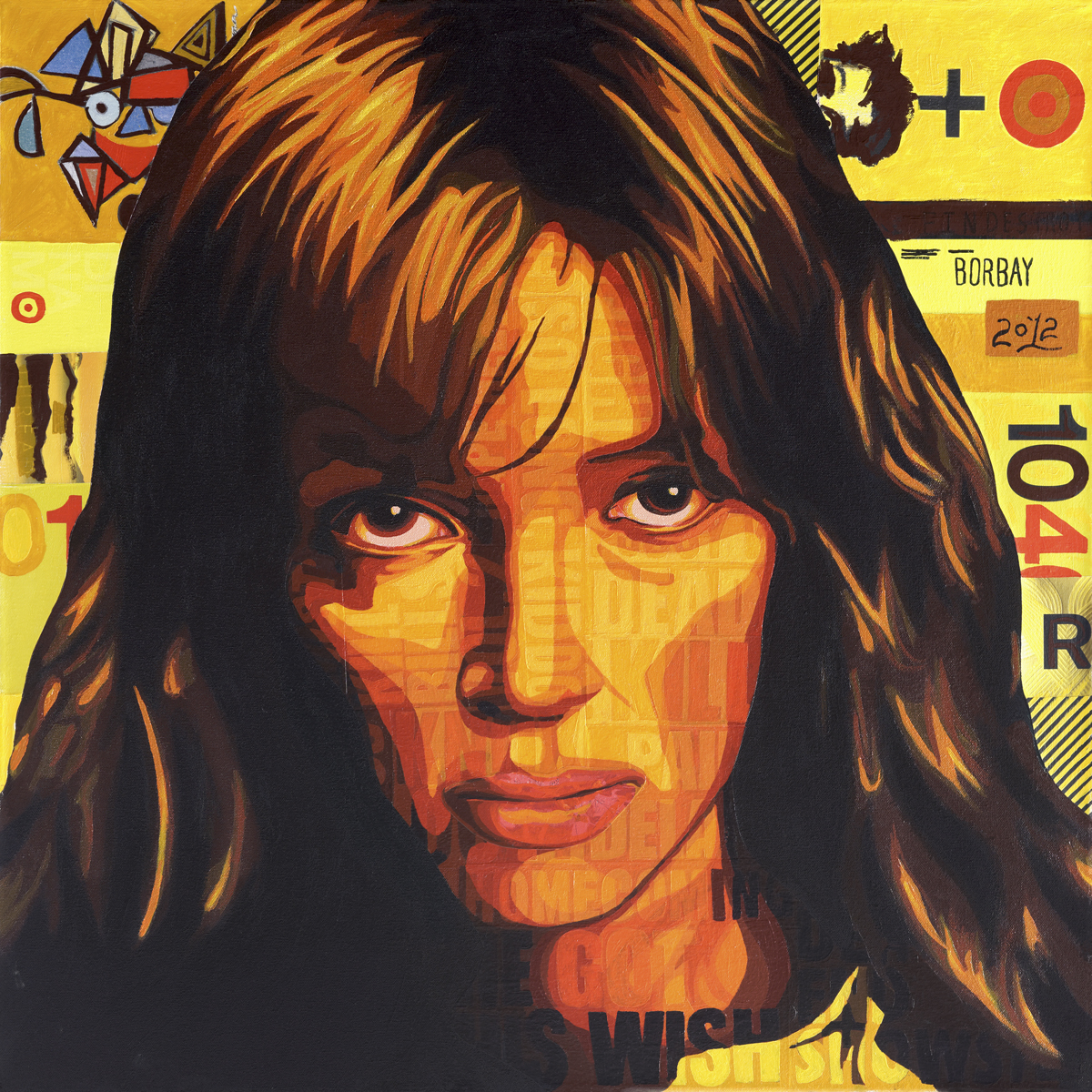

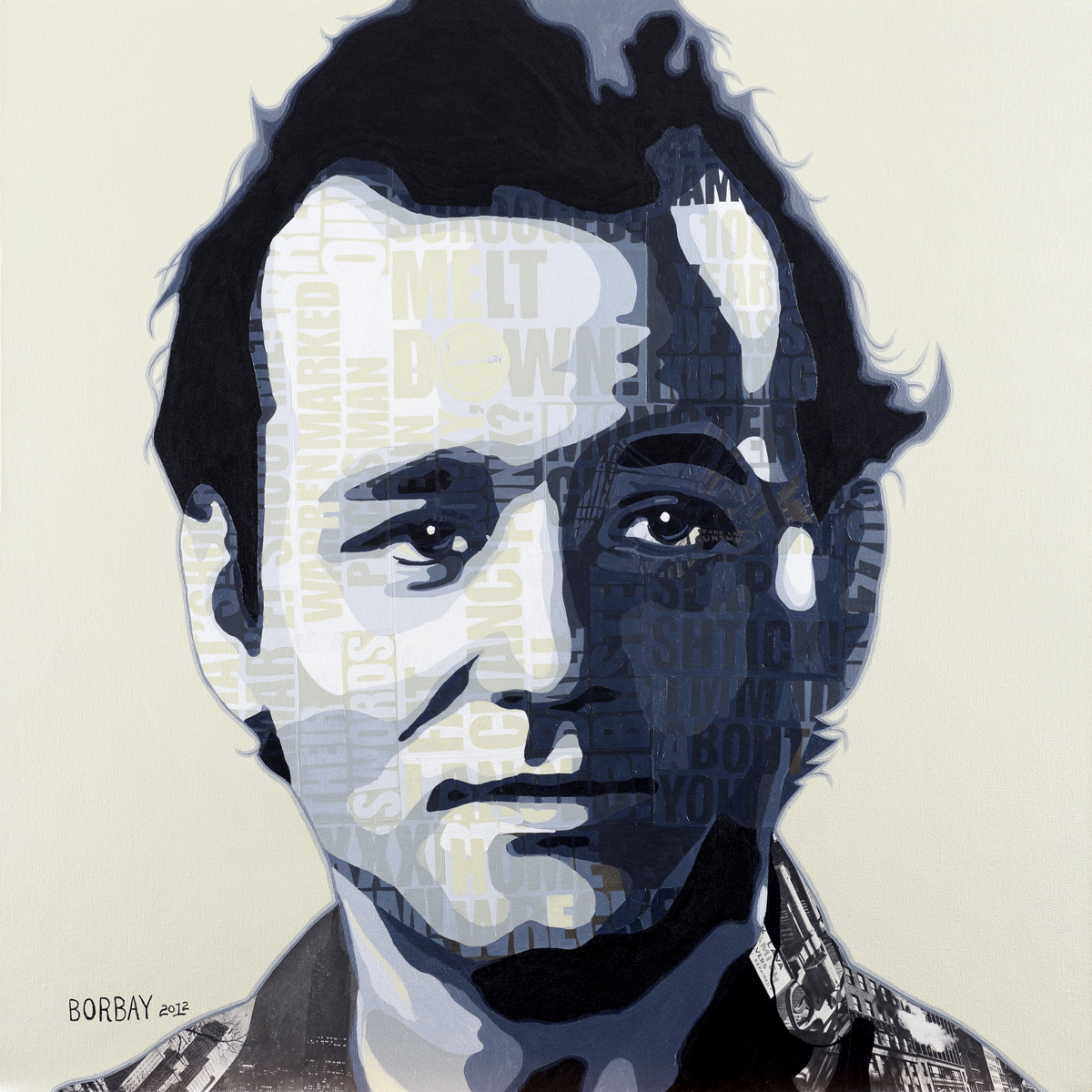

Here are some of Borbay's other portraits:

Bono | 20”X20” | 2013 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

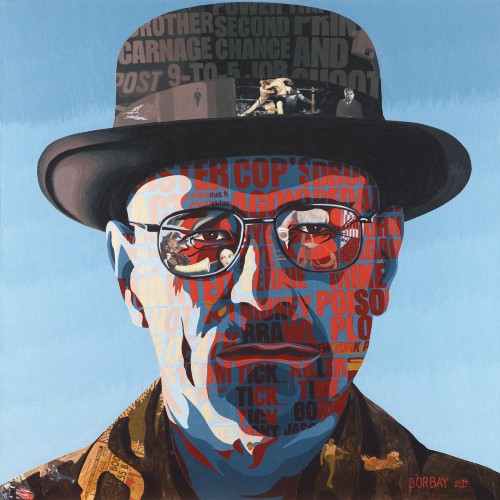

I Am The One Who Knocks | 40”X40” | 2014 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas |Process

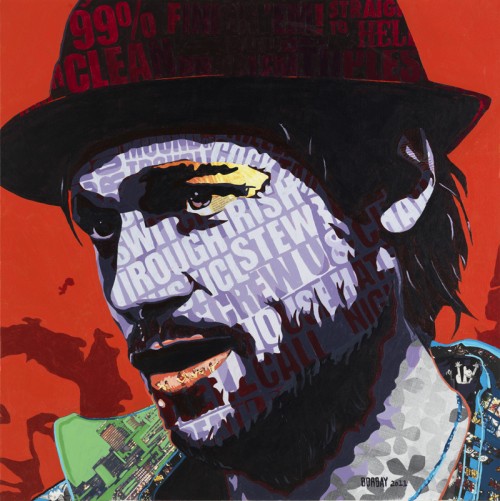

Mickey O’Pitt | 30”X30” | 2011 | Available | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Jay-Z The Portrait | 30”X30” | 2011 | Available | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

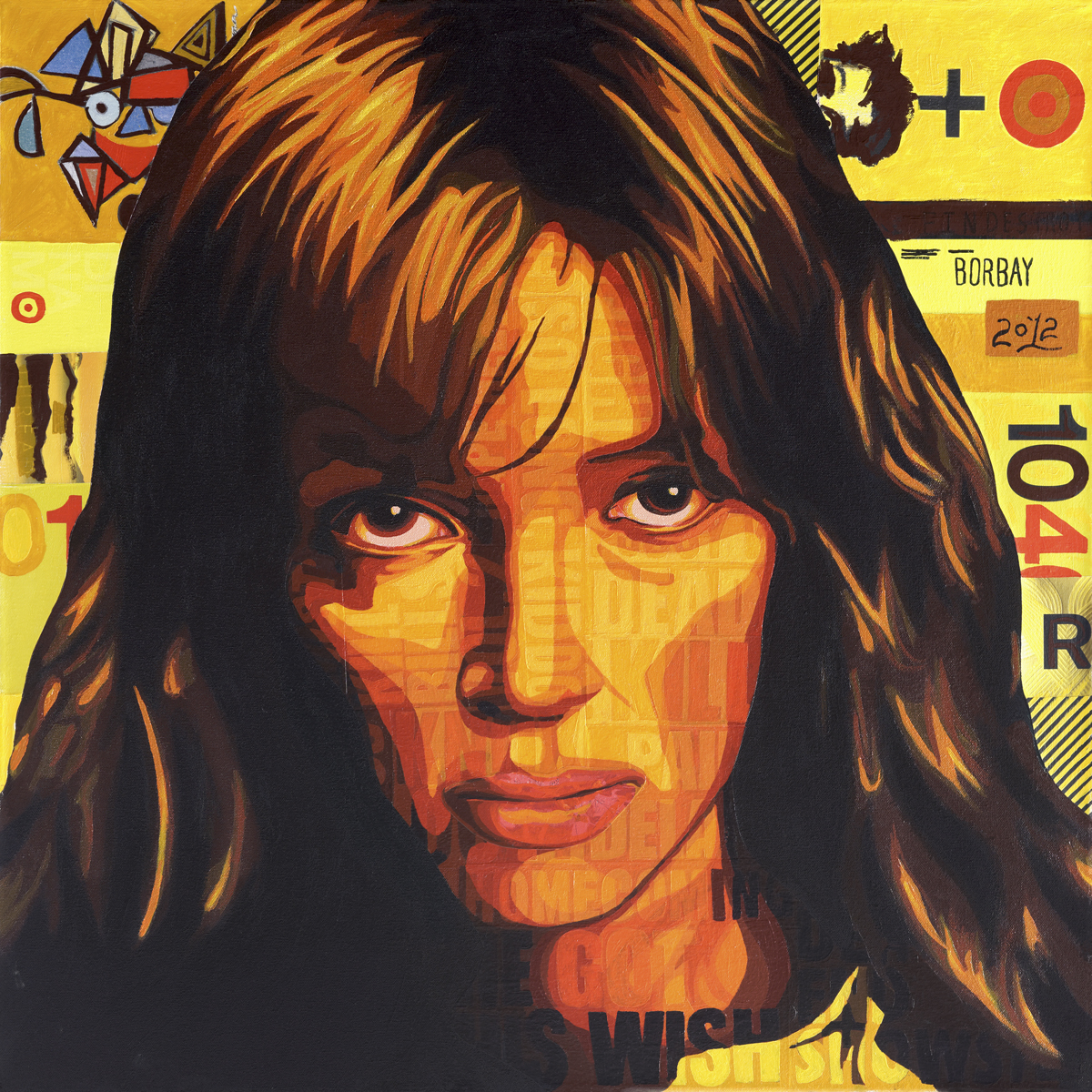

Uma Black Mamba | 30”X30” | 2012 | Available — Inquire | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

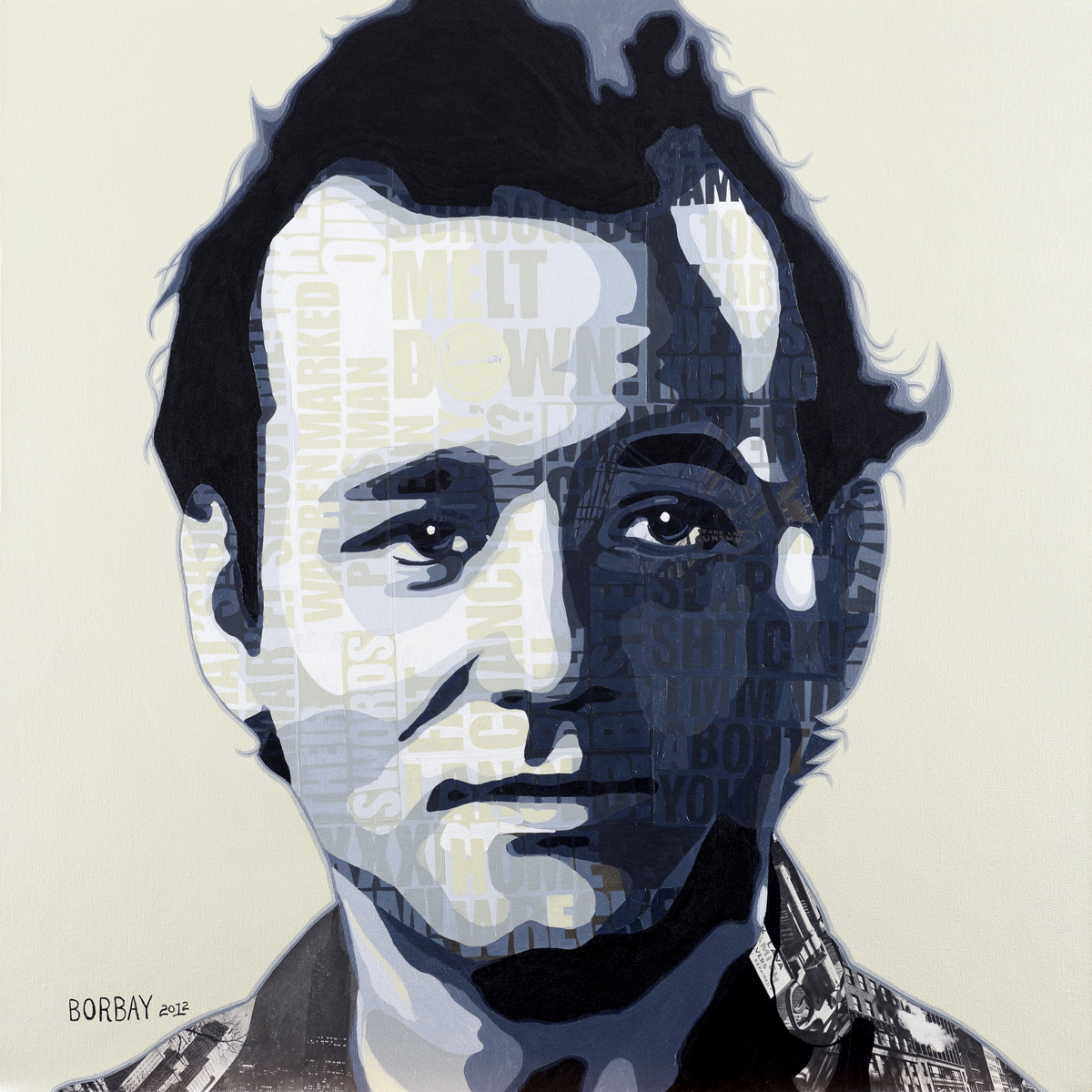

Dr. Bill Venkman | 40”X40” | 2012 | Available — Inquire | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Detective Morgan Somerset | 36”X36” | 2012 | Available | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

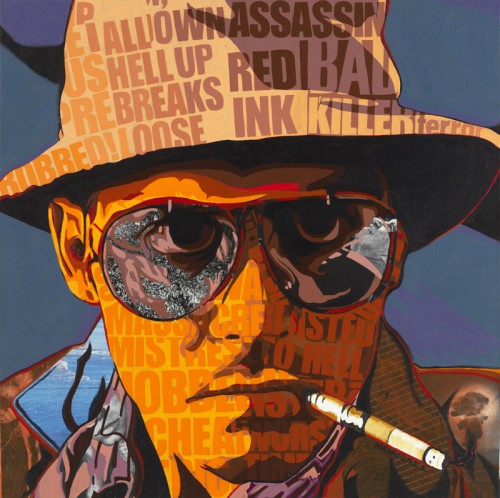

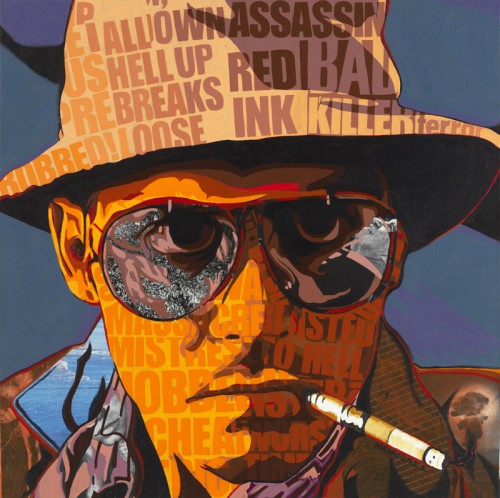

Hunter S. Depp | 30”X30” | 2011 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Bono | 20”X20” | 2013 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

I Am The One Who Knocks | 40”X40” | 2014 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas |Process

Mickey O’Pitt | 30”X30” | 2011 | Available | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Jay-Z The Portrait | 30”X30” | 2011 | Available | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Uma Black Mamba | 30”X30” | 2012 | Available — Inquire | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Dr. Bill Venkman | 40”X40” | 2012 | Available — Inquire | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Detective Morgan Somerset | 36”X36” | 2012 | Available | Buy Now | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Hunter S. Depp | 30”X30” | 2011 | Sold | Acrylic and Collage on Canvas | Process

Ashtanga

Proud Member

HQ painting .. of Michael Jackson Inc . Book Cover

Painting Details: Size: 24"X36" Media: Acrylic on Canvas

http://www.borbay.com/2014/02/24/borbay-paints-michael-jackson-inc-book-cover/

jason@borbay.com

Michael Jackson, Inc. Book Cover Painted by Borbay by Borbay

Beautiful!!!!! :woohoo:

pollys2

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2011

- Messages

- 36

- Points

- 8

Q&A: Zack O’Malley Greenburg, ‘Michael Jackson, Inc.’

http://soultrain.com/2014/05/29/qa-zack-omalley-greenburg-michael-jackson-inc/

Throughout his lifetime, books written about Michael Jackson have typically, and often repeatedly, covered the peaks and valleys and scandalous aspects of his life and career; however, for Forbes senior editor Zack O’Malley Greenburg, there is another side of Jackson worthy of exploring.

In Michael Jackson, Inc., through interviews and stories from several of Jackson’s personal and professional connections like Berry Gordy, Teddy Riley and Jackson family members, Greenburg uncovers, in intimate detail, why Michael Jackson the businessman deserves equal recognition as Michael Jackson the entertainer.

SoulTrain.com spoke with Greenburg to discuss his book that covers the highs and lows of many of Jackson’s key business moves, his influence on the entertainment industry at-large, and the intimate details and long-term effects of his acquisition of The Beatles’ music catalog.

SoulTrain.com: When you began to research and write this book, what was the big picture like for you?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: The inspiration for Michael Jackson, Inc. came out of covering the business of Michael Jackson for Forbes. After he died, I really started to notice that there was this incredible amount of cash being generated by everything related to the King of Pop and the more I followed the story, the more I realized that it was a result of business deals he made during his life, the moves he made, and the empire he built. It set me on the path of trying not to look at his financial life after death but look at his entire career from a business perspective, and the kind of moves he made and how it revolutionized entertainment.

SoulTrain.com: You spoke with many of his professional connections; how were you able to narrow it down to those included in the book? Was there anyone you wanted to talk to but couldn’t?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: It was definitely a tough process to whittle everything down into a manageable amount. There are so many people connected to his life, but I thought one of the important things to do was to condense and simplify this massive web of business connections he had over his entire life. I tried to hone in on the most relevant characters and streamline everything without sacrificing any of the specificity and detail. There are people I would’ve liked to talk to—Diana Ross is one. But Diana Ross and Quincy Jones have done so much on Michael and have talked about him so much, that I think they’re kind of tired of it! But I got to talk to a ton of people like Berry Gordy, Walter Yetnikoff, Pharrell Williams, Sheryl Crow and Jon Bon Jovi. There are a lot of juicy little anecdotes that haven’t been reported yet and I’m really excited for it to see the light of day.

SoulTrain.com: When it came to the fundamentals of business, he both directly and indirectly learned a lot from industry titans like Berry Gordy, of course, and John H. Johnson. Who would you say he pulled or drew from the most?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think Berry Gordy was really his first inspiration when it came to business. Berry told me that when he was at Motown, he was kind of doing everything simultaneously; he’d be in the studio but he’d be taking calls all the time and doing business deals. And Michael—everybody told me—was just a sponge for knowledge. He’d soak up everything and sit there and watch and listen. Berry Gordy told me that would happen a lot and young Michael would be just sitting there watching and taking it all in. I think he learned a lot by osmosis in that way.

SoulTrain.com: You note that Smokey Robinson didn’t exactly deem Joe Jackson a businessman, at least in the technical sense of the word. Surely though, beginning with the Jackson 5 and up to a certain point, Michael Jackson picked up some business know-how from his father, no?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: His father was definitely persistent. And I think that was a really important part. He pushed his kids towards perfection and that’s something that definitely stuck with Michael, for better or worse. So for sure, I think there were lessons he got from his dad, too.

SoulTrain.com: The Jackson 5 and The Jacksons made several appearances on Soul Train; in addition, Michael was interviewed by Don Cornelius many times on the show. Given this, do you think that perhaps he also observed Cornelius who, of course, was also known for his outstanding business acumen?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: That’s a good point. To be honest, that’s an angle I didn’t get a chance to explore but that certainly wouldn’t surprise me.

SoulTrain.com: To this day, Michael Jackson’s purchase of The Beatles’ catalog remains one of the biggest and most often discussed business entertainment stories ever. In the book, you note how the air surrounding this acquisition became turbulent, with many, including Jackson himself, noting that not everyone was thrilled with his ownership of it. Can you speak on this?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: Michael Jackson’s purchase of the Beatles catalog for $47.5 million is probably one of the greatest deals made in the history of the music business. Today, his stake, which is half of the Sony/ATV entity, is probably worth about $2 billion. That’s such an incredible return on investment. The thing was, at the time, people thought he was crazy and this was one of the things I found in reporting for the book: A lot of his close advisors, really successful people in the music business, thought that he was paying an outrageous sum of money and this would never be a good deal for him. But the way he looked at it was that this was like a fine work of art—like a Picasso—and in his mind, you couldn’t really put a value on something like that. It was priceless. He said these were the greatest songs of all time and he was going to get them. He made a note to [his attorney] John Branca who was negotiating with the Australian billionaire who owned the Beatles catalog—the note said, “John, please let’s not negotiate; it’s MY CATALOG.” I think that was really a turning point; not just for his business career but for entertainment, as well, where you see entertainers sort of start to go essentially from performing to being owners and employers.

SoulTrain.com: With the purchase of the Beatles catalog being a very major move, how would you say it impacted his other business ventures?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: Subsequent to that, he did a lot of things in the late 80s and early 90s, like launching his own clothing line, shoe line and record label. These things didn’t necessarily take off for him, but earned him tens of millions of dollars anyway, and it really paved the way for the likes of Diddy, Jay-Z and acts like that to have gone on to make those kinds of things almost a prerequisite for success in the music world. A lot of that dates back to Michael Jackson taking the idea of monetizing fame and completely revolutionizing it and coming up with all of these different ways artists could prosper from their celebrity.

SoulTrain.com: The book notes how Michael Jackson’s showman side and businessman side intersected when it came to his perfectionist mentality. From a business standpoint, would you say that way of thinking was a help? A hindrance?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think it’s a little bit of both. When you’re driven to be the best all the time, particularly when the standard is one you’ve already set (like with Thriller), it can sometimes be very hard to top it. By definition, it’s nearly impossible to top the greatest of anything; I mean, it’s the greatest for a reason. Thriller was the greatest selling album of all time and it’s certainly an incredible work, musically. He was obsessed with topping that from both standpoints and I think it was really damaging to him when the sales figures and the reviews for his albums weren’t quite up to that standard. I think he was very consumed with the desire to top Thriller in all possible aspects and I think that led to him sometimes delaying albums to perfect them, which in turn had an impact on some of his outside business ventures that were supposed to be picked up with the launch of these albums. I think that was definitely a theme throughout his career.

SoulTrain.com: From his die-hard to casual fans, it seems not everyone knew about his corporate savvy. Why do you think his business sense wasn’t acknowledged like his showmanship was?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think the negative publicity around him later in his life, starting with the [sexual molestation] allegations in the early 90s and going forward through to the end of his life, really overshadowed all the good things. Particularly, from a financial standpoint, I think because the media was so fixated on his financial woes and in many cases, was kind of overseeing them, that it really wiped away the truth, which was that he was quite a savvy businessman. The only reason why he was able to rack up such a large amount of debt was that he had such a vast amount of assets and was worth so much on paper because of his business savvy. He had the collateral that he needed to take out those loans; he really was like a corporation in and of himself. There are plenty of corporations out there that are worth about half as much as their assets and I think mainstream media isn’t used to that and weren’t able to grasp that in their conceptualization of him and his career.

SoulTrain.com: You detail how involved Michael Jackson was with the hip-hop community—how he often had conversations with the likes of 50 Cent and Nas—and even how R&B and hip-hop producer Rodney Jerkins learned from him how to buy catalogs. Can you expound on his connection to hip-hop?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think that’s another one of the things that comes out in this book—Michael Jackson’s impact on hip-hop. A lot of the guys I talked to—including Pharrell Williams, Swizz Beatz, 50 Cent, Nas and Diddy—all these guys will tell you that they grew up idolizing Michael Jackson and they will also tell you that he was up on every kind of music, in particularly, hip-hop, right up until the very end of his life. Diddy actually told me Michael Jackson knew hip-hop like he was born in the South Bronx in the 80s. He lived and breathed it, from the music to the dancing. He even featured The Notorious B.I.G. on HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I in ‘95 before he had really even ascended to the heights that he eventually did. He knew what was going on, he paid attention, and I fully believe that if he were around today, making new music, he would have continued to work with some of the big hip-hop acts. At the time of his death, he was working with Swizz Beatz and he was having conversations with Pharrell and Nas. I think hip-hop was a huge part of Michael Jackson.

SoulTrain.com: Through researching or writing this book, did anything surprise you along the way?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think one of the things I didn’t quite realize was just how focused Michael Jackson became on making a film career for himself in Hollywood. We started to see that with The Wiz, obviously, and then going forward with Captain EO and so forth. Around the time the allegations really turned his career upside down in the early 90s, he was well into a couple of huge movie deals. He had a couple of things in development that were going to be really big and there are some details on that in the book. I fully believe he would’ve accomplished it if it hadn’t been for the allegations because after that happened, he just became somebody who the studios didn’t really want to associate with. I really think that he could’ve had sort of an “Elvis-like” aspect to his career, as far as on the screen goes.

SoulTrain.com: What would you like readers to take away from the book?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I want people to get that Michael Jackson was not only the greatest entertainer of all time but that he was really as much a revolutionary when it came to the business of entertainment as he was when it came to the performance aspect.

http://soultrain.com/2014/05/29/qa-zack-omalley-greenburg-michael-jackson-inc/

Throughout his lifetime, books written about Michael Jackson have typically, and often repeatedly, covered the peaks and valleys and scandalous aspects of his life and career; however, for Forbes senior editor Zack O’Malley Greenburg, there is another side of Jackson worthy of exploring.

In Michael Jackson, Inc., through interviews and stories from several of Jackson’s personal and professional connections like Berry Gordy, Teddy Riley and Jackson family members, Greenburg uncovers, in intimate detail, why Michael Jackson the businessman deserves equal recognition as Michael Jackson the entertainer.

SoulTrain.com spoke with Greenburg to discuss his book that covers the highs and lows of many of Jackson’s key business moves, his influence on the entertainment industry at-large, and the intimate details and long-term effects of his acquisition of The Beatles’ music catalog.

SoulTrain.com: When you began to research and write this book, what was the big picture like for you?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: The inspiration for Michael Jackson, Inc. came out of covering the business of Michael Jackson for Forbes. After he died, I really started to notice that there was this incredible amount of cash being generated by everything related to the King of Pop and the more I followed the story, the more I realized that it was a result of business deals he made during his life, the moves he made, and the empire he built. It set me on the path of trying not to look at his financial life after death but look at his entire career from a business perspective, and the kind of moves he made and how it revolutionized entertainment.

SoulTrain.com: You spoke with many of his professional connections; how were you able to narrow it down to those included in the book? Was there anyone you wanted to talk to but couldn’t?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: It was definitely a tough process to whittle everything down into a manageable amount. There are so many people connected to his life, but I thought one of the important things to do was to condense and simplify this massive web of business connections he had over his entire life. I tried to hone in on the most relevant characters and streamline everything without sacrificing any of the specificity and detail. There are people I would’ve liked to talk to—Diana Ross is one. But Diana Ross and Quincy Jones have done so much on Michael and have talked about him so much, that I think they’re kind of tired of it! But I got to talk to a ton of people like Berry Gordy, Walter Yetnikoff, Pharrell Williams, Sheryl Crow and Jon Bon Jovi. There are a lot of juicy little anecdotes that haven’t been reported yet and I’m really excited for it to see the light of day.

SoulTrain.com: When it came to the fundamentals of business, he both directly and indirectly learned a lot from industry titans like Berry Gordy, of course, and John H. Johnson. Who would you say he pulled or drew from the most?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think Berry Gordy was really his first inspiration when it came to business. Berry told me that when he was at Motown, he was kind of doing everything simultaneously; he’d be in the studio but he’d be taking calls all the time and doing business deals. And Michael—everybody told me—was just a sponge for knowledge. He’d soak up everything and sit there and watch and listen. Berry Gordy told me that would happen a lot and young Michael would be just sitting there watching and taking it all in. I think he learned a lot by osmosis in that way.

SoulTrain.com: You note that Smokey Robinson didn’t exactly deem Joe Jackson a businessman, at least in the technical sense of the word. Surely though, beginning with the Jackson 5 and up to a certain point, Michael Jackson picked up some business know-how from his father, no?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: His father was definitely persistent. And I think that was a really important part. He pushed his kids towards perfection and that’s something that definitely stuck with Michael, for better or worse. So for sure, I think there were lessons he got from his dad, too.

SoulTrain.com: The Jackson 5 and The Jacksons made several appearances on Soul Train; in addition, Michael was interviewed by Don Cornelius many times on the show. Given this, do you think that perhaps he also observed Cornelius who, of course, was also known for his outstanding business acumen?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: That’s a good point. To be honest, that’s an angle I didn’t get a chance to explore but that certainly wouldn’t surprise me.

SoulTrain.com: To this day, Michael Jackson’s purchase of The Beatles’ catalog remains one of the biggest and most often discussed business entertainment stories ever. In the book, you note how the air surrounding this acquisition became turbulent, with many, including Jackson himself, noting that not everyone was thrilled with his ownership of it. Can you speak on this?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: Michael Jackson’s purchase of the Beatles catalog for $47.5 million is probably one of the greatest deals made in the history of the music business. Today, his stake, which is half of the Sony/ATV entity, is probably worth about $2 billion. That’s such an incredible return on investment. The thing was, at the time, people thought he was crazy and this was one of the things I found in reporting for the book: A lot of his close advisors, really successful people in the music business, thought that he was paying an outrageous sum of money and this would never be a good deal for him. But the way he looked at it was that this was like a fine work of art—like a Picasso—and in his mind, you couldn’t really put a value on something like that. It was priceless. He said these were the greatest songs of all time and he was going to get them. He made a note to [his attorney] John Branca who was negotiating with the Australian billionaire who owned the Beatles catalog—the note said, “John, please let’s not negotiate; it’s MY CATALOG.” I think that was really a turning point; not just for his business career but for entertainment, as well, where you see entertainers sort of start to go essentially from performing to being owners and employers.

SoulTrain.com: With the purchase of the Beatles catalog being a very major move, how would you say it impacted his other business ventures?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: Subsequent to that, he did a lot of things in the late 80s and early 90s, like launching his own clothing line, shoe line and record label. These things didn’t necessarily take off for him, but earned him tens of millions of dollars anyway, and it really paved the way for the likes of Diddy, Jay-Z and acts like that to have gone on to make those kinds of things almost a prerequisite for success in the music world. A lot of that dates back to Michael Jackson taking the idea of monetizing fame and completely revolutionizing it and coming up with all of these different ways artists could prosper from their celebrity.

SoulTrain.com: The book notes how Michael Jackson’s showman side and businessman side intersected when it came to his perfectionist mentality. From a business standpoint, would you say that way of thinking was a help? A hindrance?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think it’s a little bit of both. When you’re driven to be the best all the time, particularly when the standard is one you’ve already set (like with Thriller), it can sometimes be very hard to top it. By definition, it’s nearly impossible to top the greatest of anything; I mean, it’s the greatest for a reason. Thriller was the greatest selling album of all time and it’s certainly an incredible work, musically. He was obsessed with topping that from both standpoints and I think it was really damaging to him when the sales figures and the reviews for his albums weren’t quite up to that standard. I think he was very consumed with the desire to top Thriller in all possible aspects and I think that led to him sometimes delaying albums to perfect them, which in turn had an impact on some of his outside business ventures that were supposed to be picked up with the launch of these albums. I think that was definitely a theme throughout his career.

SoulTrain.com: From his die-hard to casual fans, it seems not everyone knew about his corporate savvy. Why do you think his business sense wasn’t acknowledged like his showmanship was?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think the negative publicity around him later in his life, starting with the [sexual molestation] allegations in the early 90s and going forward through to the end of his life, really overshadowed all the good things. Particularly, from a financial standpoint, I think because the media was so fixated on his financial woes and in many cases, was kind of overseeing them, that it really wiped away the truth, which was that he was quite a savvy businessman. The only reason why he was able to rack up such a large amount of debt was that he had such a vast amount of assets and was worth so much on paper because of his business savvy. He had the collateral that he needed to take out those loans; he really was like a corporation in and of himself. There are plenty of corporations out there that are worth about half as much as their assets and I think mainstream media isn’t used to that and weren’t able to grasp that in their conceptualization of him and his career.

SoulTrain.com: You detail how involved Michael Jackson was with the hip-hop community—how he often had conversations with the likes of 50 Cent and Nas—and even how R&B and hip-hop producer Rodney Jerkins learned from him how to buy catalogs. Can you expound on his connection to hip-hop?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think that’s another one of the things that comes out in this book—Michael Jackson’s impact on hip-hop. A lot of the guys I talked to—including Pharrell Williams, Swizz Beatz, 50 Cent, Nas and Diddy—all these guys will tell you that they grew up idolizing Michael Jackson and they will also tell you that he was up on every kind of music, in particularly, hip-hop, right up until the very end of his life. Diddy actually told me Michael Jackson knew hip-hop like he was born in the South Bronx in the 80s. He lived and breathed it, from the music to the dancing. He even featured The Notorious B.I.G. on HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I in ‘95 before he had really even ascended to the heights that he eventually did. He knew what was going on, he paid attention, and I fully believe that if he were around today, making new music, he would have continued to work with some of the big hip-hop acts. At the time of his death, he was working with Swizz Beatz and he was having conversations with Pharrell and Nas. I think hip-hop was a huge part of Michael Jackson.

SoulTrain.com: Through researching or writing this book, did anything surprise you along the way?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I think one of the things I didn’t quite realize was just how focused Michael Jackson became on making a film career for himself in Hollywood. We started to see that with The Wiz, obviously, and then going forward with Captain EO and so forth. Around the time the allegations really turned his career upside down in the early 90s, he was well into a couple of huge movie deals. He had a couple of things in development that were going to be really big and there are some details on that in the book. I fully believe he would’ve accomplished it if it hadn’t been for the allegations because after that happened, he just became somebody who the studios didn’t really want to associate with. I really think that he could’ve had sort of an “Elvis-like” aspect to his career, as far as on the screen goes.

SoulTrain.com: What would you like readers to take away from the book?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I want people to get that Michael Jackson was not only the greatest entertainer of all time but that he was really as much a revolutionary when it came to the business of entertainment as he was when it came to the performance aspect.

Soundmind

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 27, 2011

- Messages

- 3,667

- Points

- 0

I read the so called review on WallStreetJ , what a hateful piece of shit . I tried to comment but for unknown reason I could not.

It's astonishing to see the amount of jealousy and envy directed at MJ . The article has nothing to do with the book , it is certainly not a review of it but a rehash of the tabloids' stories for the last 30 years. The hate and envy can't be any more obvious.

Murdoch and his cronies can't allow the public to view MJ as a smart man. I will keep my mouth shut as I don't want to get banned.

It's astonishing to see the amount of jealousy and envy directed at MJ . The article has nothing to do with the book , it is certainly not a review of it but a rehash of the tabloids' stories for the last 30 years. The hate and envy can't be any more obvious.

Murdoch and his cronies can't allow the public to view MJ as a smart man. I will keep my mouth shut as I don't want to get banned.

Last edited:

Petrarose

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2009

- Messages

- 9,574

- Points

- 0

Paris78;4015329 said:Joe Vogel @JoeVogel1 · 6 h.

Much respect to @zogblog for his integrity with Michael Jackson, Inc. It's infinitely easier 2 sell sensationalism on MJ to publishers/media

^SO, So, So true. I am glad someone put that bit of information out there.

I like this part of the write up above: Jackson’s earnings prowess was so great that, even after child molestation allegations rocked his career in 1993, he recovered and had one of his best years ever in 1995. But after a second round of accusations turned into a lengthy trial in 2005, the King of Pop was unable to regain his peak financial form—in his lifetime, that is.

^^This tells me that Zack is putting the issues in context. I was wary about his book before, because I heard him on 60 minitues talking about debt due to the over-spending of the 80s. I was worried that he would just list a number of debts without putting the whole thing in to context. I mean mIchael did not have low cash flow because he went shopping every week. That is something I find missing from a lot of people's writings or statements about Michael. They tend to just give a whole bunch of statements of woe/downfall/doomsday without showing why something happened. I noticed that a lot in the trial too, but I should not digress....

I think this may end up to be one of the books I will actually read myself, rather than just buying it for others. I will see.

From the Soultrain Q&A: There are plenty of corporations out there that are worth about half as much as their assets and I think mainstream media isn’t used to that and weren’t able to grasp that in their conceptualization of him and his career.

^^I am so glad he pointed this out too. So many like to dismiss this as though Michael's situation was quite unique. It is part of their MO to discredit him professionally and artistically.

I don't think, like Zack does, that he held back on albums partly because he wanted to top Thriller. I think he was just an intense perfectionist (something Zach noted) and felt they were not up to his level of excellence. Of course I felt he wanted to top Thriller, but not that he held back the albums for that reason. I think the media trying to belittle his work constantly brought that up and made it the focal point whenever they mentioned sales of his work. I did not know he had conversations with 50 cents (who has now dropped to 1 cent), but it might not have been many conversations.

Soundmind what do you expect from the Wall Street Journal. Let's see what the NYT has to say, since Sullivan and his friends are working there.

Last edited:

"SoulTrain.com: What would you like readers to take away from the book?

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I want people to get that Michael Jackson was not only the greatest entertainer of all time but that he was really as much a revolutionary when it came to the business of entertainment as he was when it came to the performance aspect."

Yes!!!

I am looking forward to this book. Also appreciate this interview w. Soul Train and what he has to say here, esp. re how the 90's allegations upended his career in terms of his finances and business plans, although he managed to come back on top to be "right back where I wanna be--I'm standing though you're kicking me!" Glad Zack talks about how MJ wanted to make movies. I agree when he says there was so much material and so many poeople involved in MJ's life and career. Also the idea that he was in himself a corporation.

I wish in the wsj review that they would talk about MJ's charitable contributions--$300 M is not small change!

Zack O’Malley Greenburg: I want people to get that Michael Jackson was not only the greatest entertainer of all time but that he was really as much a revolutionary when it came to the business of entertainment as he was when it came to the performance aspect."

Yes!!!

I am looking forward to this book. Also appreciate this interview w. Soul Train and what he has to say here, esp. re how the 90's allegations upended his career in terms of his finances and business plans, although he managed to come back on top to be "right back where I wanna be--I'm standing though you're kicking me!" Glad Zack talks about how MJ wanted to make movies. I agree when he says there was so much material and so many poeople involved in MJ's life and career. Also the idea that he was in himself a corporation.

I wish in the wsj review that they would talk about MJ's charitable contributions--$300 M is not small change!

Soundmind

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 27, 2011

- Messages

- 3,667

- Points

- 0

http://www.forbes.com/sites/zackoma...es-inside-michael-jacksons-best-business-bet/

[h=1]Buying The Beatles: Inside Michael Jackson's Best Business Bet[/h]

A very good read

[h=1]Buying The Beatles: Inside Michael Jackson's Best Business Bet[/h]

A very good read

HIStory

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2011

- Messages

- 6

- Points

- 0

RF wrote another article , I did not read it just saw the title, all I can say the guy has lost his mind

So is he pissed by this book? Good to see. LOL.

HIStory

Proud Member

- Joined

- Jul 25, 2011

- Messages

- 6

- Points

- 0

The following is an excerpt from the new book Michael Jackson, Inc.

Once every few months during the mid-1980s, a handful of America’s savviest businessmen gathered to plot financial strategy for a billion-dollar entertainment conglomerate.

This informal investment committee included David Geffen, who’d launched multiple record labels and would go on to become one of Hollywood’s richest men after founding DreamWorks Studios; John Johnson, who started Ebony magazine and would become the first black man to appear in the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans; John Branca, who has since handled finances for dozens of Rock and Roll Hall of Famers including the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones; and Michael Jackson, the King of Pop and chairman of the board, inscrutable in his customary sunglasses.

Shares of the entertainment company in question were never traded on the New York Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. Though few would even consider it to actually be a company, this multinational’s products have been consumed by billions of people over the past few decades. Had the organization been officially incorporated, it might have been called Michael Jackson, Inc.

In 1985, this conglomerate made its most substantial acquisition: ATV, the company that housed the prized music publishing catalogue of the Beatles. Included were copyrights to most of the band’s biggest hits, including “Yesterday,” “Come Together,” “Hey Jude,” and hundreds of others. The catalogue, later merged with Sony’s to form Sony/ATV, currently controls more than two million songs by artists ranging from Eminem to Taylor Swift, making it the world’s largest music publishing company.

At an investment committee meeting months before the deal was consummated, however, the acquisition was looking unlikely. Michael Jackson, Inc. was deep into negotiations with Australian billionaire Robert Holmes à Court, whose asking price for ATV had soared past $40 million—prompting disagreement among Jackson’s inner circle over how to proceed.

Order Michael Jackson, Inc

Not wanting to upset anyone, Jackson remained silent—as he often did in meetings—but he’d already made his decision. He scrawled a note on the back of a financial statement and passed it to Branca beneath the table.

“John please let’s not bargain,” it read. “I don’t want to lose the deal . . . IT’S MY CATALOGUE.”

A few months later, Jackson bought ATV for a price of $47.5 million. Today, Sony/ATV is worth about $2 billion; through Jackson’s estate, his heirs still own his half of the joint venture. That wouldn’t be the case were it not for the shrewd maneuvering and unwavering resolve of Jackson and his team. The incredible story begins more than a quarter century ago, in the United Kingdom, during an encounter between a famous knight and a soon-to-be king.

One night in 1981 at Paul McCartney’s home just outside of London, the former Beatle handed Michael Jackson a binder. Inside was a list of all the songs whose publishing rights were owned by McCartney. After letting much of his own songwriting catalogue slip away as a youngster, he’d been buying up copyrights for years.

“This is what I do. I bought the Buddy Holly catalogue, a Broadway catalogue,” McCartney told the young singer. “Here’s the computer printout of all the songs I own.” Jackson was fascinated. He wanted to start doing the same, and his entrepreneurial instincts quickly clicked into gear. “Paul and I had both learned the hard way about business and the importance of publishing and royalties and the dignity of songwriting,” Jackson wrote in his autobiography.

When he got back to California, he found himself with an enviable problem. He’d earned $9 million in 1980 and was sitting on a pile of money that needed to be invested. Inflation was rampant in the early 1980s, meaning that fallow cash would start to lose value quickly. In short, he needed to find some worthwhile places to park the reserves of Michael Jackson, Inc.

His accountants brought him a number of real estate deals, but he wasn’t excited enough to buy anything. He wanted to buy songs. So his attorney, John Branca (now co-executor of Jackson’s estate), started talking to people in the publishing business to find out what was for sale. One of his first conversations was with songwriter Ernie Maresca, who had two big rock songs available: “Runaround Sue” and “The Wanderer.” When Branca told Jackson, the singer didn’t recognize them. The lawyer gave his client a tape and told him to have a listen. A few days later, Jackson called back. “You gotta get those songs!” he said. “I danced to them all weekend.”

Thus began a buying binge for Branca and Jackson. They picked up a small catalogue that included “1-2-3,” a 1960s soft-rock love song by Len Barry; “Expressway to Your Heart,” a Gamble and Huff composition released by the Soul Survivors in 1967; and “Cowboys to Girls,” a 1968 hit by the Intruders composed by the same duo. If Jackson didn’t know a song, Branca would send him a recording; if the singer fell in love with it, he’d give the go-ahead to acquire it.

Longtime associate Karen Langford remembers sitting around with Jackson during this period and discussing which of the greatest songs of all time would be best to own (he often mentioned ones by the Beatles, Elvis, and Ray Charles, among others). Sometimes he’d quiz Langford, singing a snippet of a song and asking if she could give the title and performer. Even then, he had his eye on ownership at a scale few could have fathomed at his age.

“He wanted to be the number one publisher in the world,” she says. “And . . . it would come up in lots of different ways, but [his goal] was always number one, getting to that number one spot. Being the biggest, being the best.”

In Pictures: Michael Jackson’s Career Earnings, Listed Year-By-Year

What the singer really wanted was Gordy’s Jobete catalogue, home to most of Motown’s greatest hits, including those of the Jackson 5. Gordy says Jackson offered him a “competitive” price for it at one point, but the Motown chief wasn’t ready to sell—and didn’t, until EMI paid him $132 million for half of the catalogue in 1997.

But watching Gordy manage his publishing interests had set something ablaze inside Jackson. “He got the bug,” says Gordy. “And that gave him the [urge] to want to do something even greater.”

***

“Michael,” began Branca, coyly, at a meeting in September 1984, “I think I heard of a catalogue for sale.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s ATV.”

“Yeah, so what’s that?”

“I don’t know, they own a few copyrights, I’m trying to remember,” said Branca, pausing for effect. Then he offered a few names: “Yesterday,” “Come Together,” “Penny Lane,” and “Hey Jude.”

“The Beatles?!” Jackson exclaimed.

The only problem: the catalogue belonged to billionaire Robert Holmes à Court, an Australian corporate raider known for a steely patience, a penchant for backing out of deals at the last minute, and a stubbornness that rivaled that of any rock star. He also had plenty of other suitors for ATV, including billionaire real estate developer Samuel LeFrak, Virgin Records founder Richard Branson, and the duo of Marty Bandier and fellow publishing executive Charles Koppelman (Bandier was hired to run Sony/ATV in 2007 and remains the company’s chief executive).

For Holmes à Court, there were few pleasures greater than a grueling business negotiation. He took particular glee in toying with overzealous Americans (“They are just looking for me to play according to their rules and make it a big game,” he once said of his stateside counterparts. “The Viet Cong didn’t play by the rules, and look what happened.” None of that mattered to Jackson. His instructions to Branca: “You gotta get me that catalogue.”

None of that mattered to Jackson. His instructions to Branca: “You gotta get me that catalogue.”

The lawyer remembers the frenzied days that followed. His first task: to check in with Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono, both friends of Jackson. As John Lennon’s widow, Ono was in charge of his estate and was rumored to have had some interest in making a joint offer for ATV with McCartney. Jackson was hoping to avoid a showdown.

“I got Yoko on the phone,” recalls Branca. “And then I said, ‘Michael asked me to call you and find out if you’re bidding [on] ATV Music that owns all the Beatles songs.’ ”

“No, we’re not bidding on it.”

“No?”

“No, no, if we had bought it, then we’d have to deal with Paul,” replied Ono. “It’d have been a whole thing. Why?”

“Because Michael’s interested.”

“Oh, that would be wonderful in the hands of Michael rather than some big corporation.” (When I asked Ono about the conversation some thirty years later—in the midst of a brief interview prior to an anti-fracking rally at New York’s ABC Carpet & Home, of all places—she said she didn’t have “a complex dialogue” with anyone on Jackson’s team, but wouldn’t elaborate.)

Branca says his next move was to check in with John Eastman, Paul McCartney’s lawyer and brother-in-law (he represented the singer along with his father, Lee Eastman, who started working with McCartney before the Beatles broke up). According to Branca, Eastman said McCartney wasn’t interested because the catalogue was “much too pricey.” This was one of many reasons that neither Branca nor Bandier believed McCartney would lay out such a large amount of cash.

Though the Beatles’ songs made up roughly two-thirds of ATV’s value, the remaining third consisted of assets McCartney didn’t want: copyrights to thousands of other compositions, a sound effects library, even some real estate. “Paul’s demeanor was very, very much more financially structured,” says Bandier. Adds Joe Jackson: “The only reason Michael bought that catalogue was because it was for sale! [McCartney and Ono] could have bought the catalogue themselves. But they didn’t.”

There’s also an artistic explanation for McCartney’s unwillingness. “I never thought Paul McCartney would buy it because it’s very difficult for a creator of something [to buy] it,” says Bandier. “It would be like Picasso, who spent a day doing a painting, to buy it for $5 million like twenty years later. It wouldn’t be a thing that Paul would do.”

In Pictures: Michael Jackson’s Career Earnings, Listed Year-By-Year

Branca opened with an offer of $30 million. But Holmes à Court wanted more, especially since Bandier, Koppelman, and a few other suitors were still interested in buying ATV. By November, Jackson had authorized Branca to raise his offer beyond $40 million. With the exception of John Johnson, Jackson’s advisors—even music executives like David Geffen and Walter Yetnikoff—thought the singer had lost his mind.

The latter told Jackson he was making a mistake and that he should stick to being an artist. “That was my advice,” says the former CBS chief. “And he disregarded it, luckily.” Jackson didn’t have a business school education, and multiples of cash flow meant little to him. But he had a tremendous sense of value—and in Branca, a lieutenant able to help him make the most of that.

“John was the financial concierge in executing Michael’s instincts,” says billionaire Tom Barrack, who’d go on to work with Jackson later in the singer’s life. “So Michael said, ‘Wow, I think there’s incredible value [in the Beatles’ songs] over time. Quite honestly, Michael didn’t know if they were worth $12 million or $18 million or $25 million. He just knew and anticipated correctly that over time the intellectual property was going to be worth a lot of money.”

Jackson’s constant refrain: “You can’t put a price on a Picasso . . .you can’t put a price on these songs, there’s no value on them. They’re the best songs that have ever been written.” During a finance committee meeting, Jackson wrote Branca the aforementioned note that still sits in the lawyer’s home: “IT’S MY CATALOGUE.”

Order Michael Jackson, Inc

A bid of $45 million was good enough to earn Jackson and Branca a meeting in London that winter, but Holmes à Court refused to go himself. Since the deal was far from being completed, Branca did the same, sending his colleague Gary Stiffelman in his stead. The two sides agreed on a nonbinding statement of mutual interest, and Jackson’s team embarked upon a four-month due diligence review of the 4,000-song catalogue.

To verify ATV’s copyrights, a team of twenty spent some 900 hours examining close to one million pages of contracts. Branca met Holmes à Court in New York that April and agreed to a handshake deal. Within weeks, however, the mogul had backed out. So, with Jackson’s blessing, Branca sent another letter: accept the last offer of $47.5 million, or there would be no deal.

Around the same time, Branca learned that Holmes à Court had tentatively agreed to sell the catalogue to Koppelman and Bandier for $50 million. But he knew his rivals—and some of the places they were getting their money. As it happened, their company had picked up a hefty publishing advance from MCA Records, headed at the time by Irving Azoff, who’d served as a consultant for Jackson and his brothers’ most recent tour.

“I went to Irving and I said, ‘How can you fund Charles and Marty? They’re bidding against Michael and you’re the consultant,’ ” Branca recalls. “[Azoff] pulled the deal, and [their ATV agreement] fell through.”

Shortly thereafter, Branca received a call from one of Holmes à Court’s colleagues. Could he come to London and close the deal? They agreed on $47.5 million. Jackson granted Branca power of attorney, and the lawyer flew to New York and boarded a Concorde bound for Britain. Once inside the supersonic jet, however, he noticed two familiar faces also on their way to London: Bandier and Koppelman.

“What are you doing over there?” Bandier asked.

“Oh,” said Branca, “just some business.”

Bandier was ready to do some business of his own. Even after Branca had convinced Azoff to pull his funding, he and Koppelman thought they could scrounge up enough capital to make a $50 million bid for ATV—and that all they needed was to buy themselves a little time. Recalls Bandier: “We actually went to London to sort of finalize a more formal contract.”

He and Koppelman figured that Holmes à Court had no interest in music publishing and was simply looking to unload ATV as quickly as possible. They weren’t counting on his patience, or the glee he may have derived from a bit of corporate sport. They certainly weren’t expecting what Holmes à Court was about to tell them when they arrived: that he was set to unload ATV to another party for $2.5 million less than they had offered.

Face to face with Holmes à Court and on the verge of losing the deal, Bandier immediately upped his offer by another $500,000. The Australian wasn’t impressed.

“There’s one aspect of the deal that you guys can’t do,” he replied. “And that is do a concert in Perth for my favorite charity.”

“We can do a charity concert,” Bandier pressed, figuring he could easily leverage his connections, and perhaps his cash, to lure just about any big act.

“No, no, you don’t understand,” continued Holmes à Court. “I’m selling this to Michael Jackson.”

***

Fittingly, Jackson had sealed his biggest deal by throwing in a personal appearance as a sweetener. It wasn’t an easy favor, either—he would have to fly fifteen hours from Los Angeles to Sydney, change planes, and then fly another five hours to Perth. But not even a pack of dingoes could have stopped him from getting his catalogue.

Bandier later learned that Jackson had offered another perk. Holmes à Court’s daughter was named Penny, and they were willing to exclude the song “Penny Lane” from the deal so that the billionaire could give it to her as a present (Jackson’s company continued to administer the song for her). It was far from a minor concession.

“Any song that you own of the Beatles earns money,” says Bandier. “There’s only like two hundred fifty of them, and everybody has a favorite of the two hundred fifty. Believe me, ‘Penny Lane’ is a popular song.” But the kicker was the appearance in Perth. “We knew that we couldn’t do the moonwalk, so there was no question,” Bandier remembers. “It wasn’t going to happen.”

Jackson’s single-minded focus on buying the catalogue despite vociferous objections from the record industry’s brightest minds might strike some as impetuous. But in hindsight, it’s clear that he was correct to follow his instincts, even to those who doubted him at first—and that his sense of the value of copyrights was impeccable.

“I think if you were his advisor at that time you would have told him, ‘Don’t do it,’ ” says Yetnikoff. “Turns out that it was a very lucrative investment. . . . So I would have to say that his business acumen is better than mine.”

Jackson certainly never forgot that he’d been right. In 2007, on a conference call with Bandier, the executive recounted the story of ATV’s 1985 sale. Jackson was delighted to relive the experience.

“See,” he said. “I told you I knew the music publishing business.”

The above text is adapted Michael Jackson, Inc, published by Simon & Schuster’s Atria imprint on June 3rd. Like the rest of the book, it is based almost entirely on original interviews; see Michael Jackson, Inc.’s bibliography for a full list of sources. For more, follow me on Twitter and Facebook.

Once every few months during the mid-1980s, a handful of America’s savviest businessmen gathered to plot financial strategy for a billion-dollar entertainment conglomerate.

This informal investment committee included David Geffen, who’d launched multiple record labels and would go on to become one of Hollywood’s richest men after founding DreamWorks Studios; John Johnson, who started Ebony magazine and would become the first black man to appear in the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans; John Branca, who has since handled finances for dozens of Rock and Roll Hall of Famers including the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones; and Michael Jackson, the King of Pop and chairman of the board, inscrutable in his customary sunglasses.

Shares of the entertainment company in question were never traded on the New York Stock Exchange or the NASDAQ. Though few would even consider it to actually be a company, this multinational’s products have been consumed by billions of people over the past few decades. Had the organization been officially incorporated, it might have been called Michael Jackson, Inc.

In 1985, this conglomerate made its most substantial acquisition: ATV, the company that housed the prized music publishing catalogue of the Beatles. Included were copyrights to most of the band’s biggest hits, including “Yesterday,” “Come Together,” “Hey Jude,” and hundreds of others. The catalogue, later merged with Sony’s to form Sony/ATV, currently controls more than two million songs by artists ranging from Eminem to Taylor Swift, making it the world’s largest music publishing company.

At an investment committee meeting months before the deal was consummated, however, the acquisition was looking unlikely. Michael Jackson, Inc. was deep into negotiations with Australian billionaire Robert Holmes à Court, whose asking price for ATV had soared past $40 million—prompting disagreement among Jackson’s inner circle over how to proceed.

Order Michael Jackson, Inc

Not wanting to upset anyone, Jackson remained silent—as he often did in meetings—but he’d already made his decision. He scrawled a note on the back of a financial statement and passed it to Branca beneath the table.

“John please let’s not bargain,” it read. “I don’t want to lose the deal . . . IT’S MY CATALOGUE.”

A few months later, Jackson bought ATV for a price of $47.5 million. Today, Sony/ATV is worth about $2 billion; through Jackson’s estate, his heirs still own his half of the joint venture. That wouldn’t be the case were it not for the shrewd maneuvering and unwavering resolve of Jackson and his team. The incredible story begins more than a quarter century ago, in the United Kingdom, during an encounter between a famous knight and a soon-to-be king.

One night in 1981 at Paul McCartney’s home just outside of London, the former Beatle handed Michael Jackson a binder. Inside was a list of all the songs whose publishing rights were owned by McCartney. After letting much of his own songwriting catalogue slip away as a youngster, he’d been buying up copyrights for years.

“This is what I do. I bought the Buddy Holly catalogue, a Broadway catalogue,” McCartney told the young singer. “Here’s the computer printout of all the songs I own.” Jackson was fascinated. He wanted to start doing the same, and his entrepreneurial instincts quickly clicked into gear. “Paul and I had both learned the hard way about business and the importance of publishing and royalties and the dignity of songwriting,” Jackson wrote in his autobiography.

When he got back to California, he found himself with an enviable problem. He’d earned $9 million in 1980 and was sitting on a pile of money that needed to be invested. Inflation was rampant in the early 1980s, meaning that fallow cash would start to lose value quickly. In short, he needed to find some worthwhile places to park the reserves of Michael Jackson, Inc.

His accountants brought him a number of real estate deals, but he wasn’t excited enough to buy anything. He wanted to buy songs. So his attorney, John Branca (now co-executor of Jackson’s estate), started talking to people in the publishing business to find out what was for sale. One of his first conversations was with songwriter Ernie Maresca, who had two big rock songs available: “Runaround Sue” and “The Wanderer.” When Branca told Jackson, the singer didn’t recognize them. The lawyer gave his client a tape and told him to have a listen. A few days later, Jackson called back. “You gotta get those songs!” he said. “I danced to them all weekend.”

Thus began a buying binge for Branca and Jackson. They picked up a small catalogue that included “1-2-3,” a 1960s soft-rock love song by Len Barry; “Expressway to Your Heart,” a Gamble and Huff composition released by the Soul Survivors in 1967; and “Cowboys to Girls,” a 1968 hit by the Intruders composed by the same duo. If Jackson didn’t know a song, Branca would send him a recording; if the singer fell in love with it, he’d give the go-ahead to acquire it.

Longtime associate Karen Langford remembers sitting around with Jackson during this period and discussing which of the greatest songs of all time would be best to own (he often mentioned ones by the Beatles, Elvis, and Ray Charles, among others). Sometimes he’d quiz Langford, singing a snippet of a song and asking if she could give the title and performer. Even then, he had his eye on ownership at a scale few could have fathomed at his age.

“He wanted to be the number one publisher in the world,” she says. “And . . . it would come up in lots of different ways, but [his goal] was always number one, getting to that number one spot. Being the biggest, being the best.”

In Pictures: Michael Jackson’s Career Earnings, Listed Year-By-Year

What the singer really wanted was Gordy’s Jobete catalogue, home to most of Motown’s greatest hits, including those of the Jackson 5. Gordy says Jackson offered him a “competitive” price for it at one point, but the Motown chief wasn’t ready to sell—and didn’t, until EMI paid him $132 million for half of the catalogue in 1997.

But watching Gordy manage his publishing interests had set something ablaze inside Jackson. “He got the bug,” says Gordy. “And that gave him the [urge] to want to do something even greater.”

***

“Michael,” began Branca, coyly, at a meeting in September 1984, “I think I heard of a catalogue for sale.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s ATV.”

“Yeah, so what’s that?”

“I don’t know, they own a few copyrights, I’m trying to remember,” said Branca, pausing for effect. Then he offered a few names: “Yesterday,” “Come Together,” “Penny Lane,” and “Hey Jude.”

“The Beatles?!” Jackson exclaimed.

The only problem: the catalogue belonged to billionaire Robert Holmes à Court, an Australian corporate raider known for a steely patience, a penchant for backing out of deals at the last minute, and a stubbornness that rivaled that of any rock star. He also had plenty of other suitors for ATV, including billionaire real estate developer Samuel LeFrak, Virgin Records founder Richard Branson, and the duo of Marty Bandier and fellow publishing executive Charles Koppelman (Bandier was hired to run Sony/ATV in 2007 and remains the company’s chief executive).

For Holmes à Court, there were few pleasures greater than a grueling business negotiation. He took particular glee in toying with overzealous Americans (“They are just looking for me to play according to their rules and make it a big game,” he once said of his stateside counterparts. “The Viet Cong didn’t play by the rules, and look what happened.”

The lawyer remembers the frenzied days that followed. His first task: to check in with Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono, both friends of Jackson. As John Lennon’s widow, Ono was in charge of his estate and was rumored to have had some interest in making a joint offer for ATV with McCartney. Jackson was hoping to avoid a showdown.

“I got Yoko on the phone,” recalls Branca. “And then I said, ‘Michael asked me to call you and find out if you’re bidding [on] ATV Music that owns all the Beatles songs.’ ”

“No, we’re not bidding on it.”

“No?”

“No, no, if we had bought it, then we’d have to deal with Paul,” replied Ono. “It’d have been a whole thing. Why?”

“Because Michael’s interested.”